Architecture, Memory, and the legacy of Design

By Viriane

I came to this exhibition out of instinct. I didn’t read a review or plan it. I just saw a poster. A Black woman standing beside a car, the colours warm, the air almost visible. I knew it was West Africa just by looking. That pull was immediate. I’ve always been interested in architecture, in colonial history, in Pan-Africanism. Not from a textbook, but from living with it.

James Barnor, Accra, 1971. Courtesy of galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière. Featured in the V&A’s Tropical Modernism exhibition.

My grandmother’s house in Abengourou, in eastern Côte d’Ivoire, is a colonial-era building. High ceilings, French-style wooden shutters, little cutouts in the walls that let air circulate naturally. The forest sings in the mornings. Light, smells, birds, insects – all of it visceral, all of it designed to breathe. It’s beautiful. It’s also history. So when I walked into Tropical Modernism at the V&A, I wasn’t just visiting an exhibition. I was walking into something familiar and complicated …

To understand Tropical Modernism, it helps to see its two parts. Modernism was a European movement that prized clean lines, minimalism, and functional beauty, design without excess. Tropical architecture, by contrast, responds directly to heat and humidity, using ventilation, shading, and natural materials to cool spaces without machines. Tropical Modernism was the meeting of both: a style born in colonised regions, blending European ideals with local climates. But that fusion was never neutral. It carried with it both innovation and the shadow of empire.

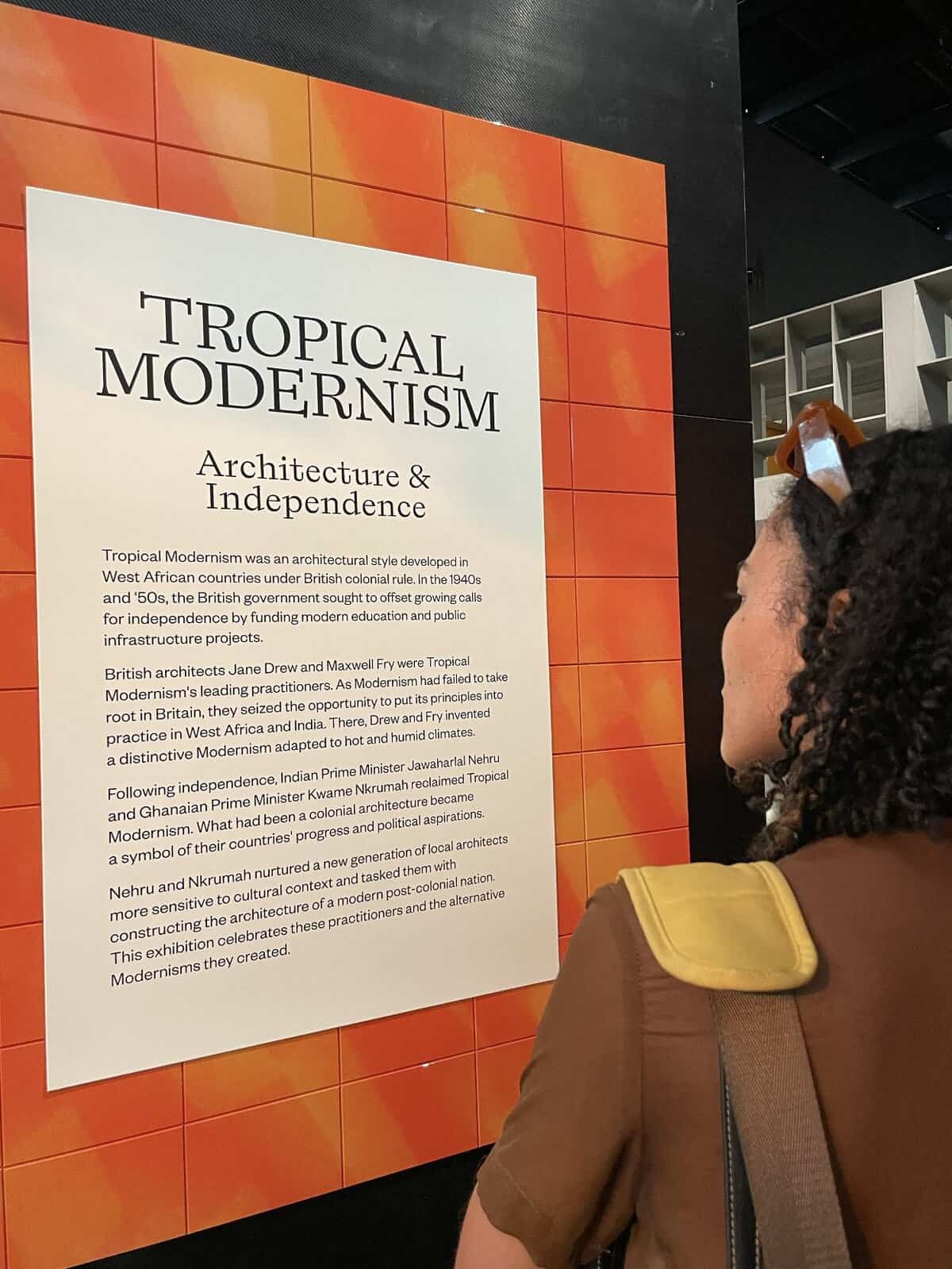

A Maze of Climate and Power

The contradictions of Tropical Modernism hit immediately. This was architecture adapted to the heat and humidity of the so-called tropics. Buildings designed to cool themselves without air conditioning. Cross-ventilation, brise soleils, wide eaves, orientation based on sun paths. It was smart. It was beautiful. It was, in many ways, sustainable before sustainability became a crisis word.

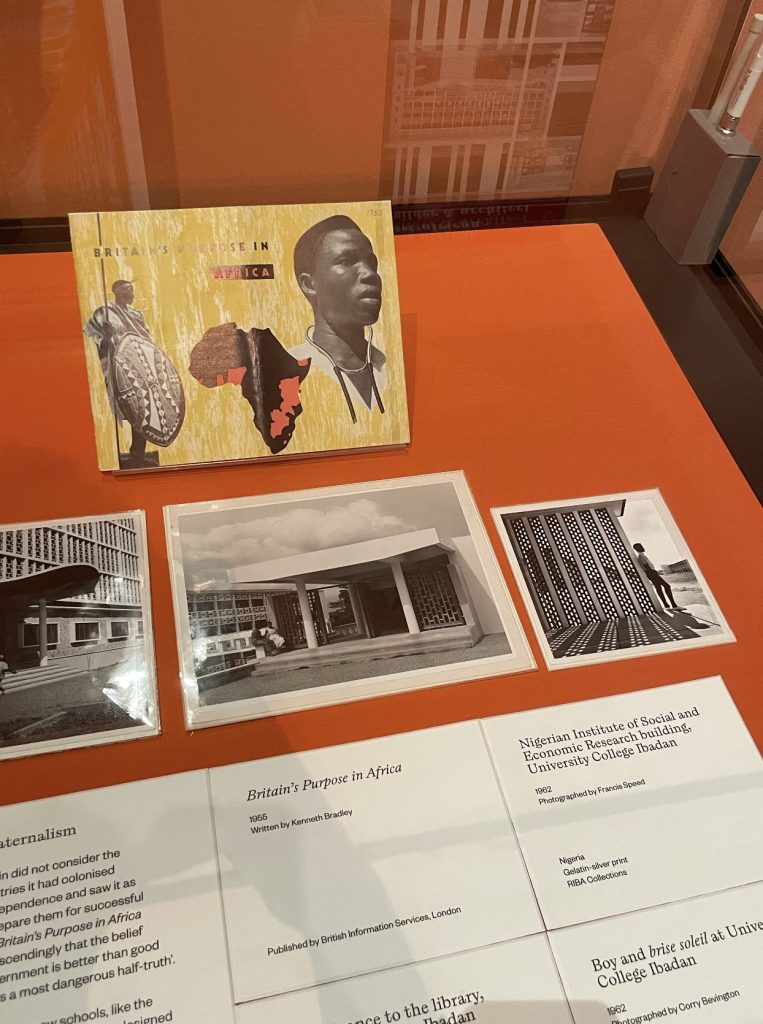

But it was also built on colonial logic. British architects like Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew came in, dismissed local building traditions as non-existent, and claimed to invent something new. They borrowed symbols like the Ashanti stool, deeply spiritual and political, and embedded them into buildings without understanding what they meant. They called it adaptation. But it looked more like decoration stripped of meaning.

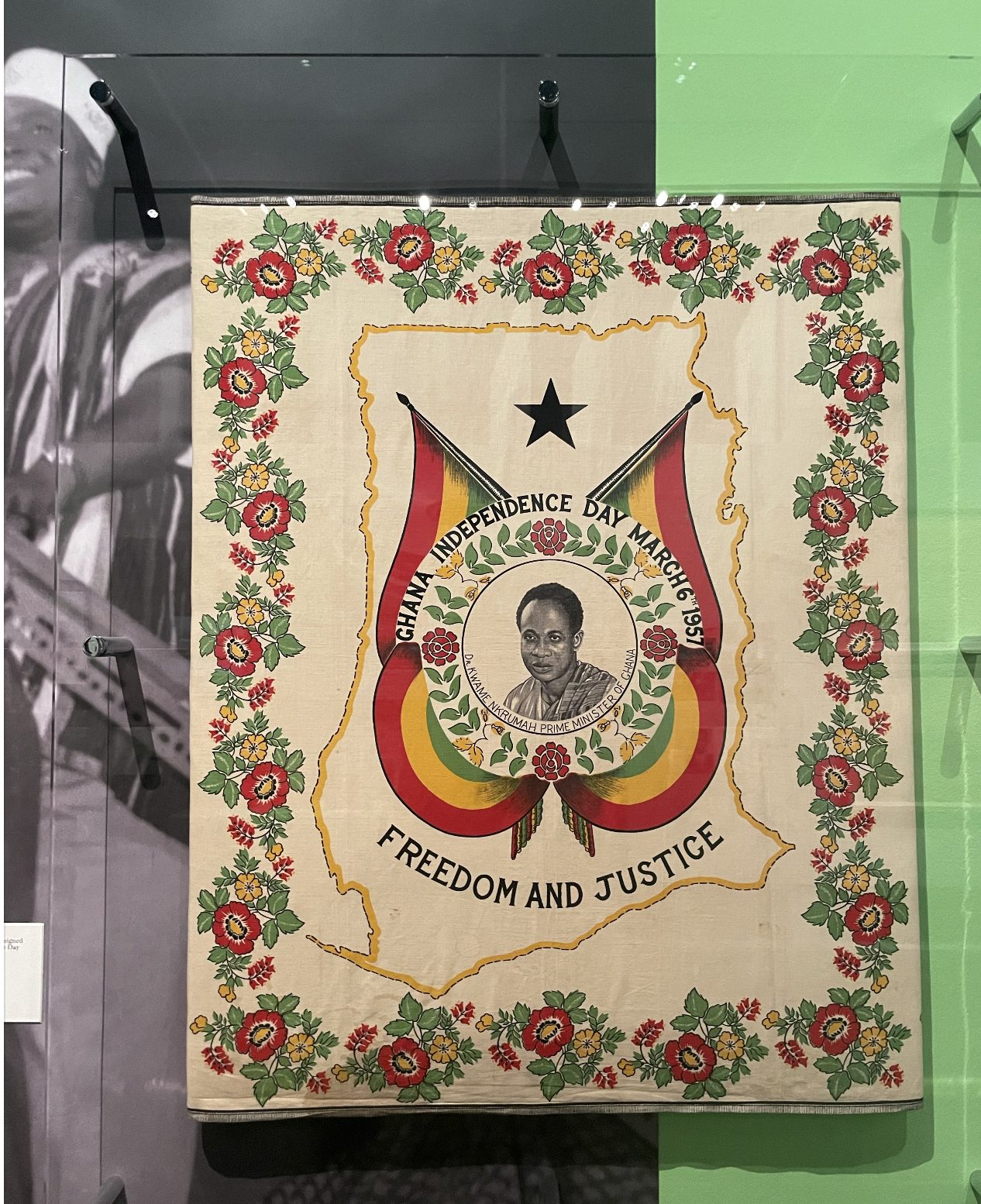

To the exhibition’s credit, it didn’t shy away from this. It acknowledged the power dynamics, the saviour complex, the uncomfortable truth that West Africa was seen as an experimental lab. A place with fewer rules, cheaper funding, and people who couldn’t say no. It also named the turning point. The rise of African independence movements, especially Ghana under president Kwame Nkrumah.

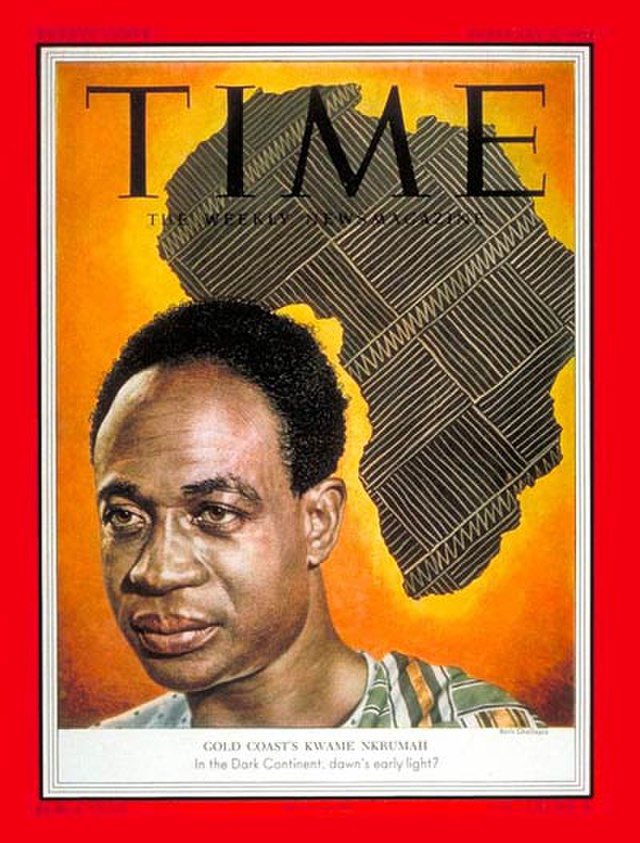

The TIME magazine cover with Nkrumah’s portrait stood out for me. I’m Ivorian, but my people are Akan, and our village borders Ghana. So when I learn about Ghana’s story, it doesn’t feel far. It feels like kin. Nkrumah’s vision of Pan-African unity wasn’t just political. It was architectural. He used Tropical Modernism as a way to show the world a new Ghana, independent, forward-looking, dignified. The fact that a colonial style could be reclaimed and made into a symbol of Black sovereignty moved me.

TIME Magazine cover featuring Kwame Nkrumah, 1953 (TIME, 1953).

African Architects and the Power of Reclaimingions of Freedom

The section on African architects came later in the exhibition, but it was powerful. Figures like John Owusu Addo, Victor Adegbite, and Max Bond were finally given space, not just as collaborators but as leaders. Nkrumah even demanded that architecture firms working in Ghana include Ghanaian principal architects. That insistence on Africanisation, not just politically but professionally, is something I deeply respect.

It reminded me of my cousin, Melissa Kacoutie, an Ivorian architect who blends traditional climate-responsive design with modern aesthetics. Her work stands in direct contrast to the mass-produced, concrete-box architecture that’s taking over Abidjan and so many cities. Developments rushed for profit, half-finished, soulless. It’s not just an African issue either. You see it everywhere, even in the UK. The idea of building something slowly, beautifully, and thoughtfully, something that breathes with the land, is becoming a rarity.

What Remains?

The exhibition left me conflicted. On one hand, I admire Tropical Modernism as a design philosophy. Its use of climate, its intelligence, its forms. On the other hand, I can’t ignore the power it was born from. But maybe that’s why I found it so personal. As someone who is mixed-race, British and West African, I understand contradiction. I live it. This style, part colonial legacy, part anti-colonial symbol, feels like a visual metaphor for that hybridity.

What stayed with me most wasn’t a specific building. It was the idea of what could have been. The dream of Pan-African unity in culture, politics, and architecture was real. And then it fell apart. Nkrumah was overthrown. Funding dried up. Air conditioning replaced intelligent design. Buildings began to rot or be demolished. But maybe exhibitions like this can light a spark again, not to romanticise the past, but to learn from it …

In an era of climate crisis, Tropical Modernism feels newly urgent. It reminds us that buildings can be both functional and beautiful, modern and local, sustainable and symbolic. That air can move through walls. That design can hold meaning.

That even in concrete, there is breathe.

References

- Barnor, J. (1971). Sick Hagemeyer shop assistant as a seventies icon posing in front of the United Trading Company headquarters, Accra, 1971. [photograph] galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière. Featured in Victoria and Albert Museum (2024), Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence. [online] Available at: https://www.galerieclementinedelaferonniere.fr/exhibitions/its-great-to-be-young-james-barnor-marc-riboud/ [Accessed 12 Aug. 2025].

- Missen, V. (2024). Personal photographs taken at the exhibition “Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence”, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2 March – 22 September 2024. [photographs].

- TIME. (1953). Kwame Nkrumah, TIME magazine cover, 9 February 1953. [image] Available at: https://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19530209,00.html [Accessed 12 Aug. 2025].